Mike’s Liberia Journal

July 2025

For the last two years, we have been working on a new large pediatric respiratory health and education project in Liberia in a partnership with the Indiana University and Riley Hospital for Children in the USA. The efforts started around this time in 2023. After almost two years of effort, I am quite excited to announce the launch of Interventions to Reduce Childhood Mortality due to Pneumonia in Liberia (IMPeL)! I just returned from Liberia and am excited to share all about it.

Interventions to Reduce Childhood Mortality due to Pneumonia in Liberia (IMPeL) –

In Spring of 2023, I met a new colleague at work: Dr. Adnan Bhutta, head of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine here at Riley Hospital for Children and Indiana University School of Medicine. Adnan has worked in pediatric global health in several locations. When he came to Riley/IU, he heard of our work in Liberia and was interested in a possible collaboration.

As you have probably heard me say in various journals and posts over the years, respiratory diseases are leading causes of illness and death worldwide, particularly in children, even more dramatically in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) like Liberia. This is one of the main reasons Partner Liberia exists and why the Liberia Respiratory Care Institute was founded. In many LMICs, the level of respiratory support, across both specialty-trained respiratory clinicians and treatment options, is limited. Often basic oxygen therapy is the highest level of support that can be given to a patient in respiratory distress. This is the case in most of Liberia. Well, most of Liberia does not have routine access to oxygen, either. But, if you go to a hospital in respiratory distress and simple oxygen therapy is not enough support to sustain you, there are not more advanced respiratory care options.

Where it’s available, a common “next option” after simple oxygen therapy for pediatric patients in respiratory distress is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). The same thing folks use for sleep apnea. But, for children, particularly young children, you can give CPAP with a very small device because they have small lungs and do not need much flow to keep them inflated. Moreover, often the pressure from CPAP is so effective at oxygenating kids that they do not need extra oxygen at all. Just the CPAP is enough.

CPAP is routinely used for pediatric patients in respiratory distress here in the States. We are not the first people to think of using it in an LMIC, either. Several countries have attempted using it, some successfully, some not. Even in Liberia, our RT graduates have always been trained to build and operate CPAP devices as part of their competency exams. There is a team from Boston Children’s Hospital who have been working with the Pediatric Department at JFK Hospital in Liberia for over a decade who have given training and brought pediatric CPAP devices. CPAP gets used, from time to time, but it has never been implemented as a part of standard care. This is often the case in other LMICs as well – someone will come introduce CPAP and train staff, it will get used for a while, and then when the trainers leave, or the physician most comfortable using it switches to a different unit, or staffing turns over, or supplies run out for the CPAP, or folks are too busy to manage the CPAP machine, or any other totally understandable reason in resource-limited situations occurs…CPAP use stops.

My colleague Adnan is also familiar with this story and struggle from his work in other countries. This is how he came up with IMPeL. He had already developed a training idea for CPAP in pediatrics in Sub-Saharan Africa when he heard about our work in Liberia. One of the most exciting things for him was the fact that Liberia has respiratory therapists, something absent in most of the rest of the continent. Adnan and I believe CPAP can make a real difference for pediatric care and more positive outcomes for kids in Liberia. Basically, we are trying to address a few of the limitations I listed above that have prevented routine use of CPAP in JFK; then, support a formal “launch” of routine pediatric CPAP use at JFK and see if this (1) is sustainable for frontline teams and (2) actually improves outcomes. The pediatric teams at JFK and Boston Children’s were quite excited about this plan, which was also crucial. Any sustainable success would require all of us working together.

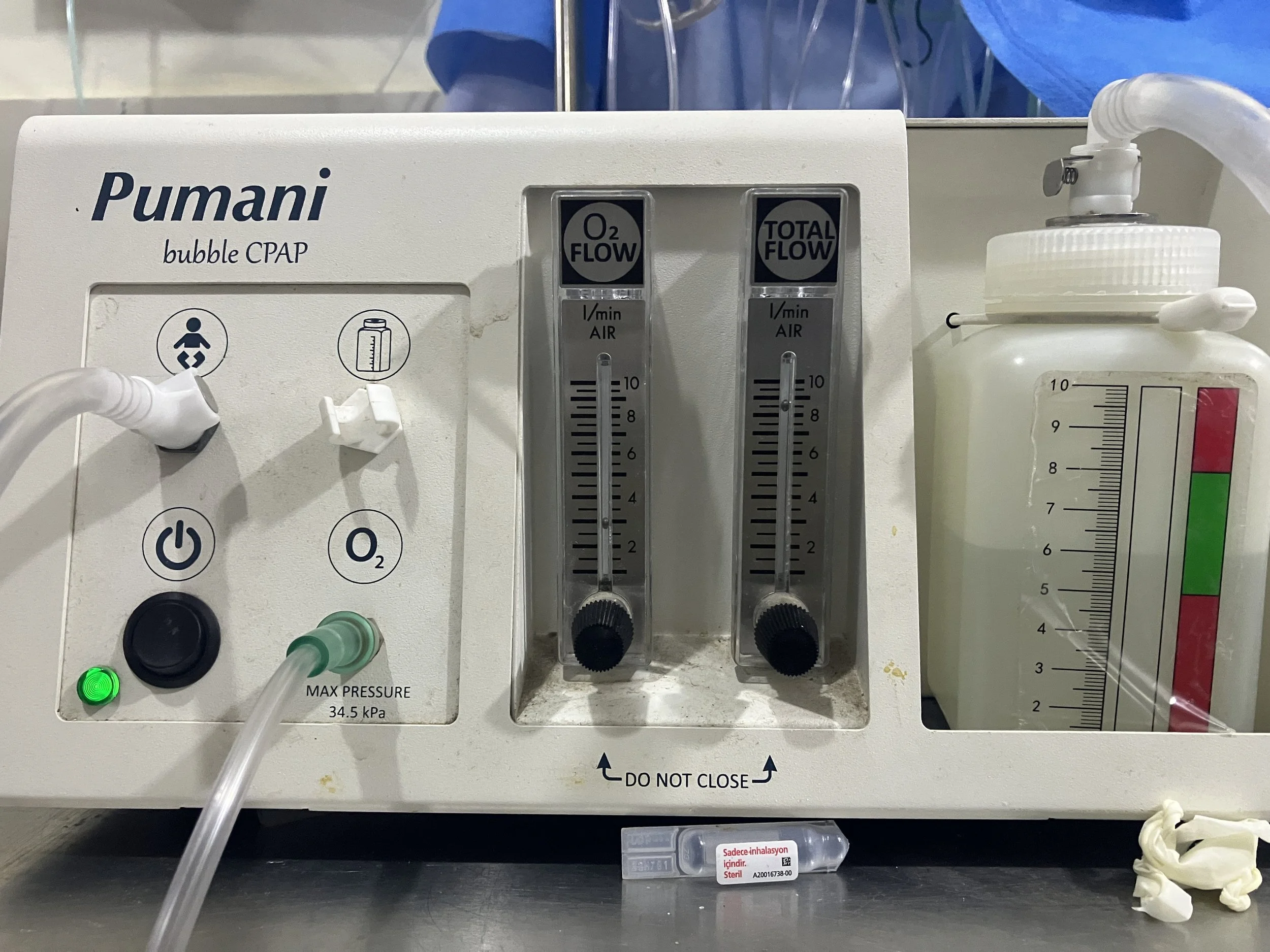

The first obstacle was to provide enough equipment to support routine use of CPAP. And, not just general equipment – the same CPAP equipment that already existed at JFK, so folks can be trained on using one interface, rather than have to memorize how multiple different devices work. There is a pediatric CPAP device designed for use in low resource settings called the Pumani (Figure 1). It is small, durable, has very few components, easy to repair, and is relatively inexpensive (a little over $1000). The Boston team had previously purchased one for the JFK Pediatric Emergency Room, where we planned to launch IMPeL (excellent, we don’t have to introduce something new!). We procured five more Pumanis and a couple of years’ worth of associated disposables and shipped those to Liberia.

Pumani bubble CPAP device

The second obstacle was to set up a standard protocol for CPAP use in the JFK Pediatric ER. We needed to establish a standard treatment protocol for the use of CPAP all parties agreed upon, train all of the pediatric faculty, and convince them to utilize it. Fortunately, Adnan had already drafted this protocol. The teams agreed with its design, so that was easy. Adnan and I worked with the JFK Peds faculty to schedule daily training sessions for the first week of our trip this spring, followed by Adnan and I rounding with them in the ER to look for patients that would benefit.

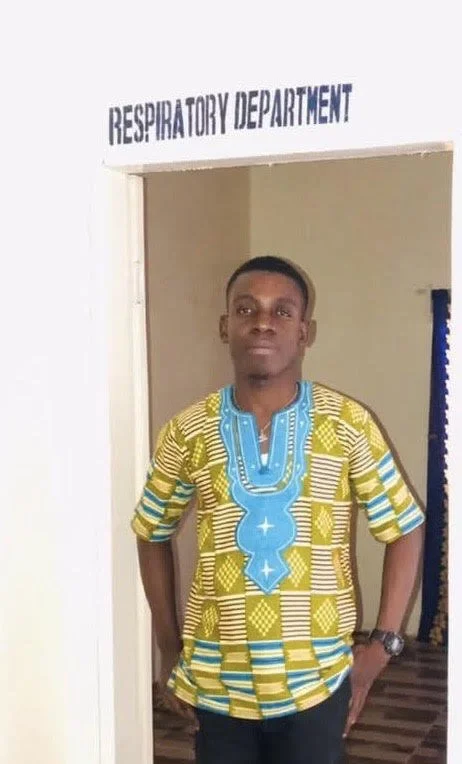

The final obstacle was finding someone on the ground to coordinate IMPeL long-term, in the absence of Adnan or myself. The physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists at JFK are overworked and understaffed; adding another job to them is not reasonable. Moreover, none of the respiratory therapists are assigned to the pediatric ER. For IMPeL to succeed, we need someone to maintain the CPAPs, provide troubleshooting support to the physicians and nurses as needed, document CPAP use over time and correspond with all parties – Partner Liberia, IU, Boston Children’s and JFK. Fortunately, we knew just the person – Ebenezer Zoefley.

Ebenezer is a Liberian Respiratory Therapist who works with Partner Liberia. He graduated from our Liberian Respiratory Care Institute several years ago and began working as a respiratory therapist. He then trained further under Joseph Moore, the co-founder of the LRCI and the first licensed Liberian respiratory therapist. Ebenezer is now the head professor at the LRCI. He also represents the respiratory therapy profession on the Liberian Medical and Dental Council, and works part time at a specialty clinic. Ebenezer was quite excited to learn about IMPeL and seemed like the perfect person to serve as the project coordinator. He is passionate about expanding respiratory care in Liberia, and he has generously volunteered his time until we can secure funding to support this work.

(Click here to sponsor)!

With these obstacles overcome, we were thrilled to launch IMPeL this spring. Ebenezer received the CPAPs and associated supplies in March and expertly assembled them in advance of our April arrival. Several members of the Boston Children’s team visited Liberia in early April and worked with the JFK Pediatrics team to prepare for the launch. Adnan and I arrived on April 27th, and formal training began on the 28th (Figure 2). Things rarely move smoothly or quickly in Liberia, but by the 30th, patients in the JFK Pediatric ER were receiving lifesaving CPAP through the new protocol (Figure 3). Adnan and I were there full-time helping to treat patients alongside the JFK Pediatrics team for a week (Figure 4). Adnan returned home, and I spent the next week gently backing off on my hands-on involvement with IMPeL, letting the local team own it while I worked on other Partner Liberia projects. Two months later and CPAP has been successfully provided to dozens of patients through the IMPeL program! Ebenezer rounds and documents daily while patients are receiving CPAP. The cadre of resident pediatricians we trained in April have changed to a different group, and IMPeL is still working.

Adnan lectures to the JFK Pediatrics team

Pediatric patient in the JFK Pediatric Emergency room receiving CPAP

Adnan and Ebenezer initiating CPAP on a pediatric patient at JFK

Beyond IMPeL, the rest of the trip was largely maintenance and preparation. The current class of students at the Liberia Respiratory Care Institute are approaching graduation and have finished their classroom studies. They are now in clinical training rotations at different hospitals around Monrovia, and they should graduate at the end of summer (Figure 5). The pause in classroom teaching has also made Ebenezer more available to provide extra support for the early months of the program before a new group of respiratory therapy students begin their classes in the fall. Unfortunately, the start of the PhD program in Biomedical Science at the University of Liberia has been delayed by funding cuts. However, the initial PhD students have been identified and selected from applications, and hopefully they will begin classes in the fall as well. I continue to serve as faculty on the committee to open the program and will work in the program once it opens.

Members of the current class of future Respiratory Therapists in clinical training rotations

Ideally, I will be visiting Liberia more frequently. I am currently planning to return in September for 2-3 weeks. The goal for the first 18 months of IMPeL is for me to visit quarterly. So, more frequent, but shorter, trips to Liberia for me. Airfare is the most significant cost for these trips, so we try to be as efficient with travel as possible, but more frequent trips are part of what we believe will ensure success of this project. Our mission at Partner Liberia is to support sustainable healthcare solutions in Liberia, particularly those related to pediatric or respiratory health. IMPeL involves both and we’re glad to be able to put Partner Liberia’s years of experience to work in this new partnership. I am really excited about this program and quite happy to see it do this well so far.

Thank you so much for your support in this work--your generous gifts and encouragement make all of this happen, and every gift matters! If you would like to donate, please click here and, as always, feel free to share these journals with anyone you think will enjoy them. We will also be posting this on social media and on our website (www.partnerliberia.org).